In the beginning, the Internet was introduced as a neutral space where the possibility of diversification of voices and thoughts would contribute to equality. To speak of a neutral space implies that there are no biases or prejudices that influence or determine its functioning. Although the most basic characteristics of the Internet propose its openness, horizontality and independence, the reality is that this is often not the case. From a gender perspective, the Internet offers enormous potential for empowerment; however, it often ends up reinforcing pre-existing inequalities, since it was created without taking into account power relations and different contexts.

Consequently, the same social problems that exist outside the digital sphere are reflected: some of them are the practices of exclusion and violence that we can see in the gender gap.

What is the digital gender gap?

It is a dichotomic concept that was first used in the 1990s to refer to the gap that appeared between countries, social groups and individuals who had access to digital technologies and those who did not. (Selwyn, 2004).

It is a dichotomic concept that was first used in the 1990s to refer to the gap that appeared between countries, social groups and individuals who had access to digital technologies and those who did not. (Selwyn, 2004).

The digital gender gap refers to the differences between men and women in access to computer equipment and in the use of electronic devices and the Internet (ICT). As we all know, many "digital divides" hide behind this term. Divisions between countries, between urban and rural areas, between women and men, old and young, rich and poor, high and low educated, literate and illiterate. There are degrees of use that depend on where it can be accessed, through what devices, with what bandwidth, at what price.

Simplifying into a binary divide tends to flatten these disaggregations, encouraging approaches that underestimate the importance of exploring differences in people's Internet experience. To be effective, policies and business plans must consider different groups on their own terms, respond to different reasons for valuing the Internet and different barriers to achieving value, and explore the relationship between those different factors. (APC, 2021).

1. Access to the internet:

According to a publication by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) in 2020 the proportion of women using the Internet globally was 48% compared to 55% of men. However, this sample has some gaps, as it claims to measure all people who have used the Internet once or more in the last 3 months. (ITU 2021).

These measurements do not include an analysis of the low percentage of women pursuing ICT-based careers, nor do they include an analysis of the working conditions on assembly lines in technology maquilas, nor do they include an analysis of the inequalities in their remuneration with respect to their male peers. (Sequera & Gimenez. 2018)

For its part, Intel Corporation published research in 2021 that women in developing countries are 23% less likely than men to connect to the Internet..

This means that in the same territory, some people are widely connected, others are less connected, and still others are disconnected. Therefore, the degree of connectivity and the quality of connection must be taken into account when measuring Internet access.

Public policy and business addressing connectivity, usage and impact must take into account the wants and connectivity needs of people in general, rather than focusing only on connecting the unconnected: on enabling those at all levels of engagement to achieve what they seek, while mitigating risks.

2. The way we inhabit the Internet:

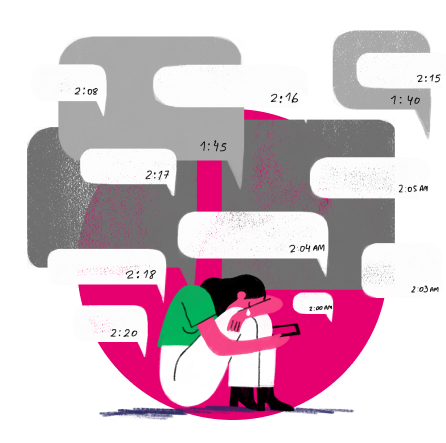

Of the people who have access, their use and way of transiting these spaces differs considerably in terms of gender. In the research conducted in Colombia (WebFoundation, 2015), it is pointed out that most women who access the Internet use it for relationships and social activities. It is also evident that a very low percentage use it as a political tool to inform and be informed. This is mainly due to the imposed hierarchy of gender roles that divides the private from the public sphere, and establishes the exclusion of women and dissenting groups from participation and decision-making. The fact that a very low percentage of women use the Internet as a means of political influence shows that gender exclusion in digital spaces responds to the same problem that generates exclusion in offline spaces. In turn, the most active women on the Internet (bloggers, journalists and activists in general) are systematically attacked online. The attacks take the form of aggressions, threats and disqualifications that allude to gender prejudices and stereotypes, as well as reinforce historical violence against women, such as threats of rape. This constitutes online gender-based violence. Such attacks generate self-censorship or cancellation of their profiles in networks. (Sequera & Gimenez. 2018).

Social inequalities are transferred to the digital spheres and in turn, violence is transferred offline. The aggressions that manifest themselves in the virtual world have a direct effect on the body and mind of those who experience them.

Thus, although the Internet is presented as a neutral space, it is not, since it is traversed by power asymmetries and political, cultural and historical moments, which subject it to the contexts in which they are produced. This lack of neutrality dates back to the moment of its creation, since hegemonic groups (cis, white, heterosexual men, belonging to high or middle social classes) are generally the ones who produce technologies. As women and minority communities are not part of the creation and production processes, inequality manifests itself not only in how we use technology but also in how technologies and the Internet operate and in what ways they are made available to society.

The regional report submitted to the Special Rapporteur on violence against women at the United Nations, provides a regional diagnosis of the situation of gender violence in the online environment, as a "continuum" of aggressions experienced by women in physical spaces -streets, universities, homes- which become more complex and amplified through the use of technology.